The Old Presbyterian Meeting House has a long and storied history. Over two centuries of faith and community have been celebrated inside these walls.

Learn about out history, buildings, people and more by clicking the links below.

Timeline

2000s

The congregation launches the Open Table program, after Washington Street United Methodist approached us about providing a hot breakfast to those in need one day a week to supplement their two day a week breakfast. Today, three churches – OPMH, Old Town Community Church [formerly Downtown Baptist] and Washington Street Methodist – provide breakfast Monday through Friday in Old Town Alexandria.

1900s

1800s

The Meeting House property is conveyed to Second Presbyterian Church and is retained by that congregation until 1949. The Meeting House is used for worship services and Sunday School classes by numerous groups, including Bethany Methodist, Lee Street Chapel, Bethel Presbyterian Mission, St. Paul’s Episcopal, Disciples of Christ, Salvation Army, ship-builders and torpedo-builders during World War I, and Second Presbyterian Church.

Flounder House provides shelter for the indigent and serves as a rental property.

1700s

When George Washington dies at Mount Vernon in December 1799, four community memorial services are conducted at the Meeting House. They are led by the Rev. William Maffit, headmaster of Alexandria Academy, the Rev. Thomas Davis, Jr., of Christ Church, the Rev. James Muir of the Presbyterian Church, and the Rev. James Tolleson of the Methodist Church. The Meeting House church bell tolls from the time of Washington’s death until his interment.

Cemetery

The Presbyterian Cemetery and Columbarium

600 Hamilton Ln., Alexandria, VA 22314

This historic cemetery, established in 1809, is still active today.

Burials occur on a regular basis, and plots and columbarium niches are available for purchase. The cemetery operates as an independent entity overseen by the Presbyterian Cemetery Board under the authority of the Session of the Old Presbyterian Meeting House.

Looking for burial arrangements, visitor access, or cemetery regulations?

Visit the official site of the Presbyterian Cemetery of Alexandria

A map of the cemetery is shown below. To explore our collection of deceased records, view headstone photographs, or find an interactive map of the cemetery, click here.

Please note that you will be asked to create a username and password to use this site.

250th Anniversary

In 2022, the Old Presbyterian Meeting House marked its 250th anniversary since the founding of the congregation in 1772. Although the festivities have ended, we share these ongoing resources. We hope you will enjoy! Consider a visit to the Meeting House for worship or another event.

A visual celebration of our congregation’s history and present ministry, with music from the Meeting House choir and musicians.

Organs at the Meeting House

Prior to the installation of the church’s first pipe organ, congregational singing and chanting of psalms was unaccompanied or supported by a string instrument.

In 1817, Jacob Hilbus and Henry Harrison of Washington, DC built and installed the church’s first organ. This organ was destroyed in the 1835 fire and was replaced in 1849 by an organ built by Henry Erben of New York City, which was installed in the apse behind the pulpit. This organ was relocated to the rear balcony in 1927. The Reuter Organ Company of Lawrence, Kansas installed an organ on either side of the Erben in 1965. In 1997, the Erben organ was returned to its original location in the apse, the Reuter organ was donated to a local congregation, and a new instrument by Lively-Fulcher Organ Builders was installed in the rear balcony.

Lively-Fulcher Organ Builders, 1997 (Balcony)

Mark Lively and Paul Fulcher have each been building organs for more than thirty years. Their goal is simply stated: To build a small number of organs, one at a time, that are of the highest artistic quality using the finest materials available.

Mark Lively has studied music, art, history, and electrical engineering. In 1976 he established the first company in the United States to utilize Computer Aided Design (CAD) in the construction of pipe organs. In 1989 he became Tonal Director of the venerable English firm of J. W. Walker and Sons. Subsequently, he was appointed Artistic Director.

Paul Fulcher, a native of England, studied piano from an early age. His training in organ building includes a formal English apprenticeship program with J. W. Walker specializing in the voicing of pipes. He worked at Walker and Sons for twenty years, eventually becoming Head Voicer and Joint Tonal Director with Mark Lively. During this period, Lively and Fulcher were responsible for building and voicing scores of organs all over the world.

Now having joined forces as partners in the US, the Lively-Fulcher organ in the Meeting House (Opus 4) has mechanical key action with a detached console and electric stop action. The mahogany case features polished tin façade (front) pipes with carved pipe shades. The organ has 31 stops, 35 ranks, and 2026 pipes.

| 16′ | 8′ | 8′ | 8′ | 8′ | 4′ | 22/3 | 22/3′ | 2′ | 11/3' | 8′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bourdon | Open Diapason | Stopt Diapason | Harmonic Flute | Principal | Open Flute | Twelfth | Cornet III | Fifteenth | Furniture IV | Open Diapason |

| 49 pipes/12 from PD 16 Subbass | 61 pipes | 61 pipes | 49 pipes/ 12 from GT Stopt flute) | 61 pipes | 61 pipes | 61 pipes | 183 pipes | 61 pipes | Trumpet | 61 pipes |

Swell to Great Tremulant

| 8′ | 8′ | 8′ | 8′ | 4′ | 4′ | 2 2⁄3‘ | 2′ | 1 1⁄3‘ | 1′ | 16′ | 8′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diapason | Chimney Flute | Salicional | Voix Celeste | Principal | Tapered Flute | Sesquialtera II | Flageolet | Larigot | Mixture III | Bassoon | Hautboy |

| (61 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (49 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (122 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (183 pipes) | (61 pipes) | (61 pipes) |

Tremulant

| 32′ | 16′ | 16′ | 8′ | 8′ | 4′ | 16′ | 8′ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contra Bourdon | Open Diapason | Subbass | Principal | Bass Flute | Fifteenth | Trombone | Trumpet |

| (digital) | (32 pipes) | (32 pipes) | (32 pipes) | (12 pipes) | (12 pipes) | (32 pipes) | (12 pipes) |

Great to Pedal

Swell to Pedal

Zimbelstern

Henry Erben, 1849 (Apse)

Henry Erben, born in 1800, was son of Peter Erben, a distinguished New York City organist of Trinity Church. At the age of seventeen, he was apprenticed to organ builder Thomas Hall, and by 1821 was a partner in the company. Upon his death, Hall’s name was dropped from the company and business for Erben was most promising. By 1845, 153 instruments had been built including six located outside the United States. From 1847 to 1863, a branch facility was maintained in Baltimore MD for the distribution of organs to the South. When Erben died in May 1884, his obituary in the New York Tribune stated that he had built 1734 organs in his career.

The Erben organ at the Meeting House is a reflection of English organs of the period. Eight-foot stops are divided on a single manual. A pedal stop was added a few years after its 1849 installation; in 1997 the pedal board and pedal bourdon were removed into storage.*

| 8′ | 8′ | 8′ | 4′ | 4′ | 2′ | 8′ | 16′ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Diapason | Stopt Diapason | Dulciana | Principal | Flute | Piccolo | Trumpet | Manual/Pedal Coupler* | Bourdon* |

We're Glad You're Here

Next Worship Services: Sunday 8:30 AM or 11:00 AM

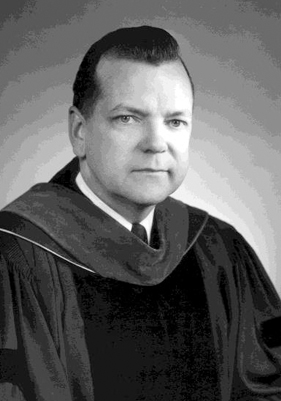

The Reverend Dr. William Randolph Sengel is called as the congregation’s ninth pastor. He leads efforts to advance social and racial justice within the church and the local community; to re-unite the northern and southern denominations of the Presbyterian Church; and to promote ecumenism. He serves our congregation until 1986 when he becomes pastor emeritus.

The Reverend Dr. William Randolph Sengel is called as the congregation’s ninth pastor. He leads efforts to advance social and racial justice within the church and the local community; to re-unite the northern and southern denominations of the Presbyterian Church; and to promote ecumenism. He serves our congregation until 1986 when he becomes pastor emeritus. The Reverend Dr. Kenneth G. Phifer (1915-1985) is called as our eighth pastor. Among his many efforts to lead the newly established congregation, he organizes a joint meeting of the presbyteries of Potomac (“Southern” denomination of Presbyterians) and Washington City (“Northern” denomination of Presbyterians) at the Meeting House in 1952, the first formal meeting of local Presbyterians since the Civil War. The Education Building, dedicated in 1957, is the congregation’s first new structure in over 120 years. In 1959, Rev. Phifer serves on the city’s Committee for Public Schools. Later that same year, he is called to the Louisville Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

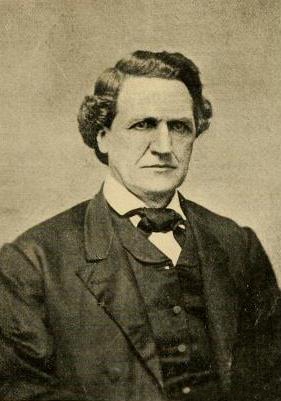

The Reverend Dr. Kenneth G. Phifer (1915-1985) is called as our eighth pastor. Among his many efforts to lead the newly established congregation, he organizes a joint meeting of the presbyteries of Potomac (“Southern” denomination of Presbyterians) and Washington City (“Northern” denomination of Presbyterians) at the Meeting House in 1952, the first formal meeting of local Presbyterians since the Civil War. The Education Building, dedicated in 1957, is the congregation’s first new structure in over 120 years. In 1959, Rev. Phifer serves on the city’s Committee for Public Schools. Later that same year, he is called to the Louisville Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky. Sponsored by Second Presbyterian Church, an independent congregation is once again created at the Meeting House. Its first worship service is led by the Rev. Dr. A. Donald Upton on the nineteenth of June 1949.

Sponsored by Second Presbyterian Church, an independent congregation is once again created at the Meeting House. Its first worship service is led by the Rev. Dr. A. Donald Upton on the nineteenth of June 1949. Following the Civil War, a series of pastors serve the congregation, each for a few years only — Reverend George M. McCampbell (1841-1918), our fifth pastor, serves from 1866 until he is called to Brick Presbyterian Church in New York City; Reverend William A. McAtee, D.D. (1838-1902), our sixth pastor, serves from 1870 until he is called to the Presbyterian Church in Hagerstown, Maryland; Reverend James M. Nourse (1840-1922), our seventh pastor, serves from 1885 until he is called to Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey.

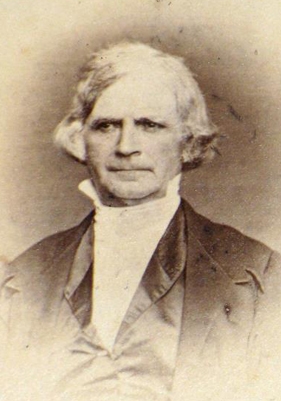

Following the Civil War, a series of pastors serve the congregation, each for a few years only — Reverend George M. McCampbell (1841-1918), our fifth pastor, serves from 1866 until he is called to Brick Presbyterian Church in New York City; Reverend William A. McAtee, D.D. (1838-1902), our sixth pastor, serves from 1870 until he is called to the Presbyterian Church in Hagerstown, Maryland; Reverend James M. Nourse (1840-1922), our seventh pastor, serves from 1885 until he is called to Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in Elizabeth, New Jersey. The Reverend Elias Harrison, D.D. (1790-1863) is called as our fourth pastor. He serves the congregation for forty-three years through the tumultuous period that culminates in the Civil War. He heads the Alexandria Academy; presides over the Board of Guardians of the Free Schools; is a founder of Alexandria’s Lyceum, its Orphan Asylum, and Female Free School; directs the Alexandria Library Company; and is a national director of the American Colonization Society.

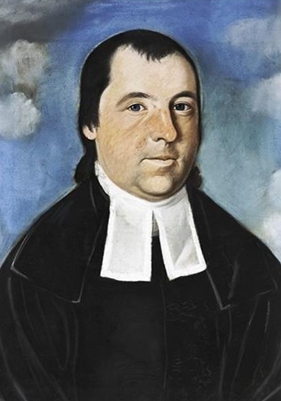

The Reverend Elias Harrison, D.D. (1790-1863) is called as our fourth pastor. He serves the congregation for forty-three years through the tumultuous period that culminates in the Civil War. He heads the Alexandria Academy; presides over the Board of Guardians of the Free Schools; is a founder of Alexandria’s Lyceum, its Orphan Asylum, and Female Free School; directs the Alexandria Library Company; and is a national director of the American Colonization Society. The Reverend James Muir, D.D. (1757-1820) is called as the congregation’s third pastor. Born in Scotland, he serves the congregation for thirty-one years, and assists in establishing the Alexandria Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, Alexandria Library Company, Alexandria Relief Society, Onesimus Society, Washington Society of Alexandria, Board of Guardians of the Free Schools, and the Bible Society of the District of Columbia. He founds and edits The Monthly Visitant, and negotiates with the British to save Alexandria during the War of 1812.

The Reverend James Muir, D.D. (1757-1820) is called as the congregation’s third pastor. Born in Scotland, he serves the congregation for thirty-one years, and assists in establishing the Alexandria Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, Alexandria Library Company, Alexandria Relief Society, Onesimus Society, Washington Society of Alexandria, Board of Guardians of the Free Schools, and the Bible Society of the District of Columbia. He founds and edits The Monthly Visitant, and negotiates with the British to save Alexandria during the War of 1812. The Reverend Isaac Stockton Keith, D.D. (1755-1813) is called as our second pastor. He serves as the founding president of the Alexandria Academy, an early experiment in providing schooling without regard to gender, race, or ability to pay. Four Presbyterian ministers succeed him as president or headmaster, and its scholars (students) are publicly examined at the Meeting House. He serves here until 1788 when he is called to serve a congregation in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Reverend Isaac Stockton Keith, D.D. (1755-1813) is called as our second pastor. He serves as the founding president of the Alexandria Academy, an early experiment in providing schooling without regard to gender, race, or ability to pay. Four Presbyterian ministers succeed him as president or headmaster, and its scholars (students) are publicly examined at the Meeting House. He serves here until 1788 when he is called to serve a congregation in Charleston, South Carolina.